Don’t Be a Slave to the Scale

Does the following story sound vaguely familiar to any of you? You wake up and look in the mirror. You are delighted to find that your physique is looking very good. Your see that your body is leaning out nicely and your muscles are shaping up well. You put your workout attire on and pleasantly discover that the clothes are fitting you very well – snug in all the right places and loose where it matters. You hit the gym and kick some serious butt, setting strength records in multiple exercises. A couple of gym members pay you compliments, informing you that you are looking fantastic. Everything is going great, and your day is off to an excellent start. Then, you step on the scale, and all of your glee comes to a screeching halt. You’ve gained a few pounds, and knowing this absolutely ruins your day.

In the past, I have heard (mainly female) clients say similar things. After telling them how great they looked or how well they’re doing, they mentioned that although they’re happy with their strength gains and physique improvements, they’ve packed on a few pounds since they started training and are therefore disappointed and discouraged with their training.

Some people don’t care so much about what the scale says – they’re more influenced by other parameters such as how they look in the mirror, how their clothes feel, what the body fat results show. However, others are laser-focused on scale weight. Anecdotally, this scenario applies to a higher percentage of women than men, but some men will certainly be able to relate. It seems that many individuals have a target weight that they’re aspiring to reach, and they just cannot be content knowing that the scale isn’t congruent with this ideal notion (or moving toward this ideal notion), regardless of whether other forms of feedback appear to be promising.

Perhaps this number represents the body weight that the individual was at when they felt they looked their all-time best (an example being wedding day). Or maybe the number represents the body weight of their favourite celebrity, model, or athlete. Nevertheless, allow me to explain you why you might indeed gain bodyweight following resistance training, but this is not necessarily a bad thing.

It’s All About the Diet

Let’s start with the obvious: when you start lifting weights, you can either lose weight, maintain weight, or gain weight. How your body responds to strength training is largely influenced by your diet. If you’re eating like a bird, you’ll lose weight, and if you’re eating like a horse, you’ll gain weight. However, lifting weights will cause you to retain more muscle while you lose weight on a caloric deficit, and it will cause you to build more muscle while you gain weight on a caloric surplus. If you want to lose weight but find yourself gaining weight, then you’re eating too much. If you want to gain weight but find yourself losing weight, then you’re not eating enough. Got it? Good! Let’s move on.

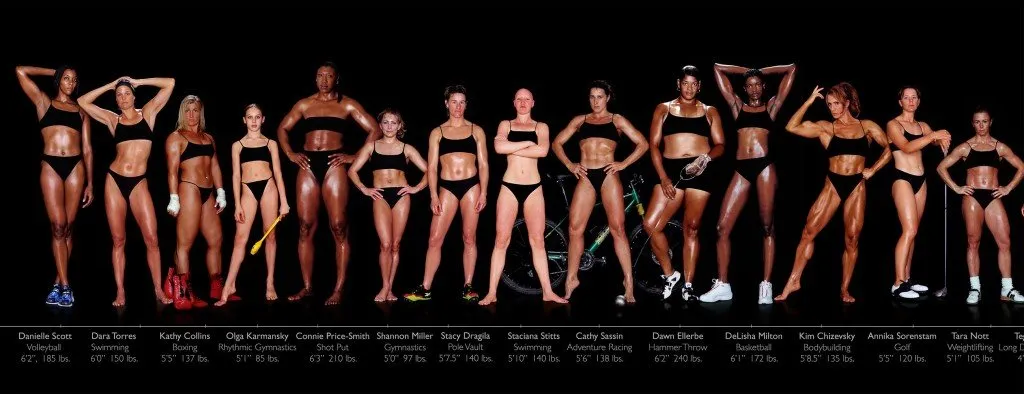

Click on the picture and look at women; each of these athletes exercise a lot, but when adjusting for height, we find that the smaller women consume much less calories than the larger women.

Intracellular Water Gain: Pumping Up the Muscles

What if we said that we possessed a syringe filled with a special fluid that when injected into the muscles, would immediately improve their body shape? This special fluid would have no negative side effects and is legal. Would you consider using it? Luckily, that’s not necessary. There is indeed a special fluid that does precisely this, and its name is water. But instead of injecting water into the muscles, all you have to do is lift weights. This causes intracellular water gain (the body’s reaction to strength training).

Yes I know most of our female readers seeing the term “water gain” and associating it with bloating, such as that experienced during pre-menstruation. However, the location of water storage largely determines whether the water retention positively or negatively impacts the physique – not all water retention is equal. There is no doubt that bloating, characterised by increases in extracellular water storage, negatively alters appearance. However, the opposite is true with regards to intracellular water storage.

Perhaps you’ve heard of bodybuilders describing how their muscles were flat. Much of what they do during the peaking phase prior to competition is designed to make the muscles appear full and the rest of the body appear dry. This is achieved by directing some of the body’s water content out of the interstitial space and into the muscle cells, which greatly enhances appearance. But this doesn’t just apply to bodybuilders. Think about the look of your favourite athletes – their muscles are probably full and shapely. As it turns out, this enhanced shape isn’t just attributable to increased muscle proteins; increased water also influences the size and shape of your muscles.

Here’s how it works. Your body contains a lot of water. Males possess a range of 38.5 – 73.5% water content, with an average water content of 58.3%, whereas females possess a range of 27.4 – 70.9% water content, with an average water content of 48.5%. So in general, humans are around 50% water.

Immediately following a strength training workout, your muscles will acutely retain water. In fact, 4 and 52 hours following a workout, your muscles will store 7 and 8% more water, respectively, and this increased water storage is associated with a 13 and 16% increase in cross sectional area, respectively. This is in line with longitudinal research which shows that total body training performed 3 times per week for 16 weeks leads to 7.5% and 7.6% increases in total body water content for men and women, respectively. Furthermore, athletes that regularly perform resistance training tend to have lower densities of fat-free mass due to the increased water storage in their muscles. What’s fascinating is that extracellular water content doesn’t increase; only intracellular water content does, by 8.2% for men and 11.0% for women, respectively. The concurrent increases in skeletal muscle mass were 4.2 and 3.9% in men and women, respectively.

How is this so? The increased water storage is highly related to increased muscle glycogen. Following 5 months of heavy resistance training, muscle glycogen increases by 66%. It is thought that every gram of glycogen stored in the muscles will bring along 2.7 grams of water along with it, with other estimates as high as 3-4 grams. Interestingly, after just 3 days on a very low carbohydrate diet, glycogen stores in the body can decrease to 1/3rd of their initial values, and following this up with a high carbohydrate diet will cause these same individuals’ glycogen levels to rise by a factor of 6, essentially doubling their initial values. These fluctuating glycogen levels create the illusion of rapid fat loss and regain, but it’s really mostly water level fluctuation. And though most estimates put total body glycogen levels at approximately 400 grams, some individuals possess over 1,000 grams of glycogen in their bodies. This information helps provide clarity as to why individuals subjected to ketogenic very low calorie diets tend to lose 4.5kg’s in just 4 days, with the top responder losing 8kg’s (in other words; the effects of ‘crash diets’)

Strength Training Makes You Denser, Up to a Point

Let’s put this into perspective. Let’s say a 65kg woman undergoes a 3-month resistance training regimen. During this time, her weight stays the same; she doesn’t lose any weight or gain any weight. But she looks markedly different in the mirror. How can this be? If she trained properly, she would have likely gained a few pounds of muscle mass, she would be storing more water in her muscles due to the increased glycogen, she would have lost several pounds of fat, and other small changes will have taken place such as increased bone density. Powerlifters tend to have the highest bone densities ever recorded, but this would be a minor factor in this example. Maybe she lost 3kg’s of fat, gained 1.5kg’s of muscle, and is storing 1.5kg’s more water in her muscles. This will markedly influence aesthetics, despite zero change in body weight.

When you strength train, weight tends to be subtracted from “bad” areas and added to “good” areas, and this shift in body composition makes a huge positive difference in your physique. And since muscle is 18% more dense than fat, improving body composition will decrease your overall volume. Since density equals mass divided by volume, you can see that increasing density without increasing mass can only be achieved by decreasing volume. Check out this 6 year progression of a female’s body shape during training, you’ll note that after just over a year, her weight didn’t change drastically, but she got smaller in overall size due to body re-compositioning.

Again, click on the picture and see what is the body shape you want without looking at the weight.

What About Exercise and Hunger Hormones – Why Am I So Darn Hungry All the Time?

If you’ve ever dieted down while undergoing resistance training and cardio, then you know how difficult it is to keep losing weight. If you’ve lifted weights competitively (as a powerlifter, weightlifter, or strongman) for any number of years, then you know how hard it is to stay a certain weight and avoid going up a weight class. But what does the research say about this? There’s a TON of intriguing research on body weight set point theory. The body seems to have a set range of weight or set range of body fat percentage that it wants to remain at, and the internal mechanism is located in the brain, and the more weight or fat you lose, the harder it is to maintain that new weight or body fat percentage.

With regards to appetite hormone effects of exercise, there really isn’t much to go by since the vast majority of the research is short term in nature. For example, 2 days of intensive resistance training has been shown to significantly decrease leptin and ghrelin levels. Twelve weeks of exercise showed that aerobics were more effective than strength training at satisfying hunger. Aerobic and resistance training suppress hunger for 1-2 hours after the training session, but this might be the case with men more so than women. Moderate and high intensity exercise appears to effect hunger hormones similarly. On a simple level that’s about all we know as yet; there is yet to be a high quality long term trial conducted on hunger hormones following resistance versus aerobic training.

Should We Even Weigh Ourselves?

The answer to this question is yes, you should weigh yourself. Well, you should as long as it doesn’t make you crazy!! Research overwhelmingly shows that daily self-weighing can be good for weight loss; that breaks in this routine can lead to increased risks of weight gain. However, the scale is just one indicator that on its own fails to capture the entire picture and you should pick one that both suits your goal and that you’re happy measuring yourself by.

What Indicators Should We Pay Attention To?

You should rely on a variety of indicators of fitness progress, including:

• scale weight

• body fat levels

• measurements

• strength levels

• how clothes fit

• progress pictures

• compliments from others

• how fit and conditioned you feel

• Health measures such as blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, insulin sensitivity, inflammation, etc.

I have dealt with clients that turn up to the gym frustrated at the scale reading when looking at their weight, then a few days later with a huge smile on her face. They have put a pair of once snug work pants on and found that there was an inch and a half gap in the waist area; they have looked at some progress pictures and could clearly see major improvements in their physique. A husband, friends, and co-workers are complimenting them and so on; it is important not to just use the scales!!

Conclusion

Self-weighing is a good idea, as long as it doesn’t cause you to feel loco en la cabeza. But if you only rely on the scale to inform you of your progress, you will be missing the forest for the trees, getting so caught up in the minutia that you fail to see the big picture. Everybody knows that resistance training does a body good and makes the body look better. Lifting weights will cause you to lean out, become denser, and lose overall volume. It will also cause your muscles to tome and swell so they have the coveted athletic look that so many desire. This muscular swelling is associated with some weight gain, so don’t sweat it if you gain a few pounds when you begin training. It’s caused by increased muscle glycogen storage and subsequent increased water storage.